Performing Copyright: Part Five

How the Statute of Anne 1710 Transformed Ownership of Plays in Print

This is the fifth of a series of posts marking the publication of my book Performing Copyright: Law, Theatre and Authorship (Oxford: Hart, 2021). In these pieces I explain the book’s core themes and key case studies, addressing how theatre’s authorship and performance practices have helped shape - and have been shaped by - historical and contemporary copyright law. My book is available here. A sample chapter is available for free download here.

In the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras dramatists had largely lacked control over print and performance of plays. As explored in my prior post, the idea of the Elizabethan theatrical author as a possessive public agent was rarely expressed - it was only really visible in the atypical figure of Ben Jonson. Post-Restoration, this began to change, with the Statute of Anne 1710 playing a key role in transforming the position of the theatrical author.

The emerging law of copyright coincided with a continuing shift towards recognising individual authorship in theatre, which created a presumption of originality on the part of the increasingly professionalised writer.[1] Over time dramatists began to benefit financially from the new legal form of authorship; and a more authorial view of composition took hold.[2]

By the end of the eighteenth century the acceptance of Romantic ‘genius’ authors as owners was well under way, not just in theatre, but in literature and music as well.[3] Yet, the Statute of Anne did not protect a ‘copyright work’ in the modern sense of a broad bundle of rights – only print was given statutory protection, with performance falling outside the scope of the Act.

Before we assess the Statute itself, it is worth considering the period prior to its passing – namely, the era that followed the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

The Changing Nature of Theatre and the Playwright’s Status, Post-Restoration (1660‒1709)

The theatres were closed from 1642‒60 during the English civil war and the rule of Oliver Cromwell. After the restoration of Charles II in 1660 the theatre market was revived – but in an altered state. Post-1660 the theatre market became more heavily regulated and restricted than it had been under Elizabeth I, James I or Charles I. Charles II issued a monopoly (patent) to two theatres ‒ one run by William Davenant (Duke’s Company) and the other by Thomas Killigrew (King’s Company).[4]

These were known as the ‘Patent Theatres’. Only these two could stage performances of serious dramas (though other theatres could perform comedy and pantomime).[5] Notably, women were allowed to perform on stage for the first time; and female playwrights – such as Susan Centlivre – began to receive attention.[6]

Yet the great blossoming of English Renaissance theatre – typified by the polyvocal productions of the late 16th and early 17th centuries – was over: collaborative writing between playwrights declined. The theatre environment was transformed to a context where individual authors were increasingly appreciated and rewarded. This manifested itself most obviously in changes to the way plays were catalogued. During the period up to the 1650s this was mainly via mere lists of titles of plays, signalling that the plays themselves, rather than authors, were the commodity for sale in print; but by the time of Gerard Langbaine’s catalogues of the 1680s–1690s the organizing principle had shifted from play to author.

In other words, the theatrical marketplace had changed to the benefit of the dramatist. Even if their plays are not as critically lauded today, post-1660 writers such as Dryden, Otway, Lee, Behn, and later, Congreve, Vanbrugh, and Farquhar, gained ‘a contemporary esteem equal, even superior, to their illustrious predecessors Shakespeare, Jonson, and Fletcher’.[7] This increased further from 1699 when it became more common for playwrights to be identified in playbills.[8]

This esteem had consequences for ownership. The idea that the playwright ought to be viewed as ‘owner’ of the text - a rare idea during the English Renaissance - became ‘a matter of heated dispute from the 1660s onwards’.[9] In material terms, we can observe this via the existence of the Restoration ‘benefit’ – a custom of giving a portion of revenues from the playhouse’s third night to the author as payment for a play.[10]

As the 1700s began there was a rise in public consumption of works of literature and drama. The need to have ‘a single identifiable author with a known body of work became an increasingly important sales pitch’.[11] In the aftermath of the ‘glorious revolution’ of 1688–89 and the Act of Union 1707, regulation of the right to copy in Britain by Parliament, in the form of legislation, would soon come to pass.

The Statute of Anne 1710 and the Recognition of Authors as Owners

Although the concept of an author’s literary property under common law had been present in judicial reasoning in the mid-to-late 17th century it nonetheless remained of ambiguous legality.[12] This change in 1710 when the first copyright statute – the Statute of Anne – came into force.[13] The Act can be viewed as the foundation of legislative copyright in the modern UK and the common law world.[14]

Why was the Act passed? The need for a copyright statute arose due to substantive conditions central to the print industry,[15] such as evolving printing technology, the demise of the previous system of state licensing, and a rapidly expanding market for books and play texts (and later, sheet music).[16] The Statute of Anne provided that the owner of the book’s ‘copy’ possessed ‘the sole liberty of printing and reprinting’ it. An infringer would be liable to ‘forfeit such Book or Books, and all and every Sheet or Sheets’ giving the owner the right to ‘forthwith Damask and make Waste Paper of them’.[17] The rationale behind the Statute of Anne was concerned primarily with ‘books’ and their ‘proprietors’ (the Stationers) rather than authors. Book publishers assumed they would continue to assert control of cultural production.

Nonetheless, over time the law had the effect of empowering authors. Although the 1710 Act was intended to protect publishers’ interests rather than those of writers, the Act nonetheless anticipated the emerging importance of the author’s role. As Bently notes:

The 1710 Act refers to ‘authors’ and makes the continuation of the copyright term from 14 to 28 years dependent upon the author’s survival … Additionally, the Stationers’ use of the claims of authors in inducing Parliament to pass the Statute indicates that authorship also had some rhetorical power.[18]

In making the author’s role visible, the Act made explicit the logic of the author as owner of common law literary property in pre-1710 court rulings involving the Stationers, while also limiting the duration of copyright.[19]

In the theatrical context, references to the role of the author in legislation can be seen in the light of the playwright’s improved economic status at the dawn of the 1700s, which in turn inspired new conceptions of what constituted authorship.[20] The material and the philosophical worked in tandem as technology and trade allowed post-Enlightenment ideas about the individual to circulate in print, helping to create a new respect for authorial ‘geniuses’.[21]

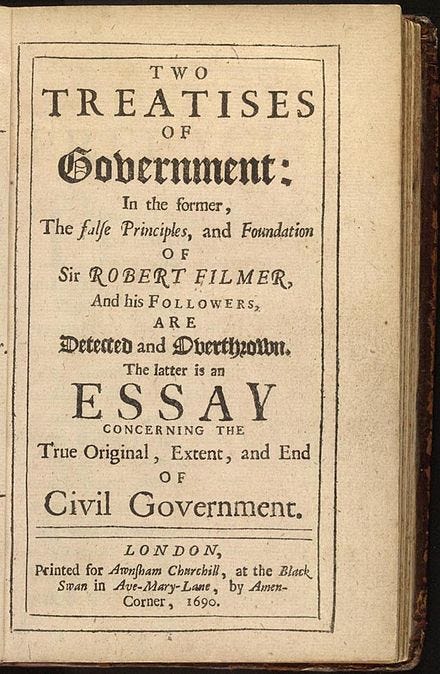

John Locke’s Two Treatises of Government (1689), which advocated a theory of individual labour-property rights as natural rights, was an influential contemporary text.[23]

Rose ties Locke’s labour theory of property individualism to the later Romanticism of Coleridge.[24] Lockean property discourse ‘which speaks of a natural right of property in the products of labour’ was thus blended with a growing acceptance that ‘heroic’ individual authors create literary, musical and dramatic works of art.[25]

Copyright law’s framing of authorship in the late 18th century was thus influenced by a critical ferment – the confluence of the material and the philosophical.[22] Our modern understanding of the theatrical author ‒ in terms of the literary imaginary and legal personhood under copyright ‒ was consolidated. As Woodmansee remarks, the legacy is that ‘a piece of writing or other creative product may claim legal protection only insofar as it is determined to be a unique original product of an intellection of a unique individual (or identifiable individuals)’.[26] By the dawn of the 19th century the theatrical author-figure as legal owner had become the norm.

As I outline in my next post, the law at the beginning of of the 19th century did not yet protect performances - only print was given statutory protection, with performance falling outside the scope of the Act. This would be altered by new legislation in 1833 and 1842.My book is available here. A sample chapter is available for free download here.

[1] P Kewes, Authorship and Appropriation: Writing for the Stage in England, 1660‒1710 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998). See however JD Litman, ‘The Invention of Common Law Play Right’ (2010) 25 Berkeley Tech. L. J. 1381, 1395 noting that the Act ‘made no immediate observable difference in the lot of dramatists’.

[2] E Cooper, ‘Copyright and Mass Social Authorship: A Case Study of the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary’ (2015) 24 Social & Legal Studies 509.

[3] FM Scherer, ‘The Emergence of Musical Copyright in Europe from 1709 to 1850’ (2008) 5 Review of Economic Research on Copyright Issues 3, 11.

[4] D Ganzel, ‘Patent Wrongs and Patent Theatres: Drama and the Law in the Early Nineteenth Century’ (1961) 76 PMLA 384‒96. In 1661 Davenant’s ‘Duke’s Company’ was based at Lincoln’s Inn Fields but in 1671 moved to Dorset Garden. In 1663 Killigrew’s company was based at Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. In Dublin, the Theatre Royal opened its doors in 1662. In 1682 the King’s Company was taken over by Duke’s to form United Company with Thomas Betterton. Betterton later received a licence from William III to found a new theatre, first at Lincoln’s Inn in 1695 and in 1720 the Theatre Royal Covent Garden. Samuel Foote founded the Theatre Royal, Haymarket, in 1766, which became the third patent theatre, operating in summer. As the 1700s went on further letters patent were granted to theatres: Theatre Royal, Cork (1760), Theatre Royal, Bath (1768), Theatre Royal, Liverpool (1772), Theatre Royal, Bristol (1778) and Theatre Royal, Birmingham (1807).

[5] The patent monopolies on the performance of serious plays lasted until their revocation via the Theatres Act 1843 (6 & 7 Vict., c. 68).

[6] DP Fisk, ‘The Restoration Actress’ in SJ Owen (ed), A Companion to Restoration Drama (Oxford: Blackwell, 2001) 69‒91.

[7] P Kewes (n 1).

[8] T Stern, ‘“On each Wall and Corner Post”: Playbills, Title-pages, and Advertising in Early Modern London’ (2006) 36 English Literary Renaissance 57.

[9] T Stern, ‘Review of Authorship and Appropriation: Writing for the Stage in England, 1660‒1710’ (2002) The Scriblerian 73.

[10] ibid. Stern acknowledges that a similar benefit existed pre-Restoration in the 1620s but notes that it became more of a norm post-1660.

[11] ibid.

[12] HT Gómez-Arostegui, ‘Copyright at Common Law in 1774’ (2014) 47 Conn. L. Rev. 1. For a Scottish perspective on the debate see H MacQueen, ‘Literary property in Scotland in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries’ in I Alexander and HT Gómez-Arostegui (eds), Research Handbook on the History of Copyright Law (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2018) 119–38.

[13] An Act for the Encouragement of Learning by Vesting the Copies of Printed Books in the Authors or Purchasers of Such Copies during the Times Therein Mentioned 1710 (Imp) 8 Anne, c 19. (Statute of Anne), available at http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/anne_1710.asp.

[14] D Ross, ‘Copyright and the Invention of Tradition’ (1992) 26 Eighteenth-Century Studies 1.

[15] D Hunter, ‘Musical Copyright in Britain to 1800’ (1986) 67 Music and Letters 269, 274.

[16] J Raven, ‘The Book Trades’ in I Rivers (ed), Books and Their Readers in Eighteenth-Century England: New Essays (London: Continuum, 2001) 1‒34.

[17] Section 1 of the Statute of Anne 1710.

[18] L Bently, ‘Copyright and the Death of the Author in Law and Literature’ (1994) 57 The Modern Law Review 973, 975.

[19] Stationers v Seymour (1677) (1677) 1 Mod. 256; Stationers v Bradford (12 June 1700) C37/692; and Stationers v Partridge (1709) HLS MS 1109.

[20] T Stern (n 9).

[21] D Saunders, ‘Dropping the subject: An argument for a positive history of authorship and the law of copyright’ in B Sherman and A Strowel (eds), Of Authors and Origins (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1994) 95‒96.

[22] B Salter, ‘Taming the trojan horse: an Australian perspective of dramatic authorship’ (2009) 56 Journal of The Copyright Society of The USA789, 792.

[23] J Locke, Two Treatises of Government (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988) (originally published 1689). See also S Stern, ‘From Author’s Right to Property Right’ (2012) 62 University of Toronto Law Journal 29.

[24] M Rose, Authors and Owner ‒ The Invention of Copyright (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993).

[25] M Chatterjee, ‘Lockean Copyright versus Lockean Property’ (2020) 12 Journal of Legal Analysis 136.

[26] M Woodmansee, ‘On the Author Effect: Recover Collectivity in The Construction of Authorship’ (1992) 10 Cardozo Arts & Ent. L.J. 279.